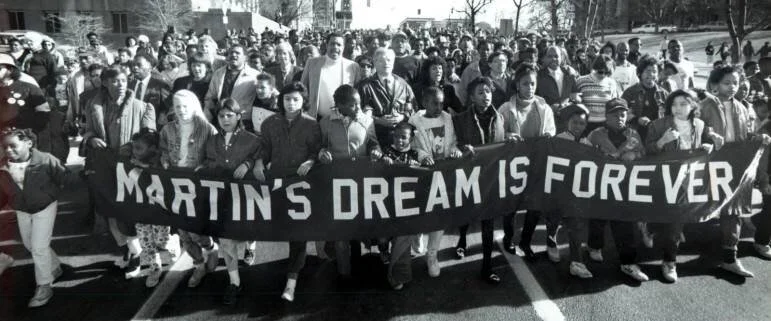

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. always expected to be killed for his stand on civil rights. On April 4, 1968 at the age of 39, he was assassinated by a rifleman in Memphis Tennessee. King had been a leader in the movement since the age of 26.

At the time of his death, he was the co-pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta with his father, Daddy King.

King had been the most visible figure leading the movement for over a decade, but it had already been showing signs of division. Stokley Carmichael had been advocating for a more direct approach for gaining civil rights. He would eventually go on to form the Black Panther Party. Other primary voices in this era would advocate for various approaches.

Many voices were critical of King’s opposition to the war in Vietnam. Many leaders in the Black community did not support King’s pivot away from focusing on black rights and instead focusing on addressing poverty in our nation across all people groups.

Dr. King was killed in Memphis because he was in town to advocate for equal rights among sanitation workers. King joined a march which began to turn violent. No longer could King require everyone to go through specialized non-violent training before being involved. Loud voices said that they could no longer afford to take a Sunday School approach to the problems of American society.

King was in a difficult spot. Black American citizens were beginning to grab onto movements rooted in anger and riots, such as the Watts riots in LA were starting to take place. King still wanted to lead his fellow Black Americans in peaceful protest, but many in the Black community that the nation was slow to address the problems which existed due to prejudice and segregation - whether official or de facto.

Some in the white community were pointing to such instances of violence as proof that Black Americans were inherently violent and not ready for integration.

King was attempting to bridge these gaps, and while he strongly advocates for personal responsibility of the actions of those in the black community, you can see King desperately trying to get the white community to see that they are abdicating their own responsibility.

He worked to explain to the white community that cries of Black Power and riots are not the causes of white resistance, they are the consequences of it. He would argue that Black citizens were becoming hopeless due to so much white resistance. In his final book, Where Do We Go From Here, he cites a magazine article naming places that are worse 10 years into the civil rights movement. Baltimore is specifically named.

To my fellow white Christians who live in the Baltimore area who would say: well, look at what is happening in Baltimore. Better to leave “them” there, King would say “It is a strange and twisted logic to use the tragic results of segregation as an argument for its continuation.”

The history of redlining in Baltimore seems to have a very clear impact on the nature of the city today. Again, each person does bear personal responsibility, but it is also true that to insist there was no disadvantage is wholly wrong.

King challenged those who refused to acknowledge the fruit of an unfair setup for hundreds of years by saying, “A society that has done something special against the Negro for hundreds of years must now do something special for him.”

He also defended the action of peaceful protestors against those who would continue to criticize or would counsel that the Black American should just wait for things to get better. He understood that it was a struggle which would have to go on. He wrote on this multiple times in his final book, saying:

“Structures of evil do not crumble by passive waiting. If history teaches anything, it is that evil is recalcitrant and determined, and and never voluntarily relinquishes its hold short of an almost fanatical resistance. Evil must be attacked by a counteracting persistence, by the day-to-day assault of the battering ram of justice.”

And again:

“Freedom is not won by a passive acceptance of suffering. Freedom is won by a struggle against suffering.”

King would say to those who assumed things will just get better: reexamine why you believe that to be the case.

But King understood that as long as this was a black versus white dynamic, the Black American would likely never receive the dignity and opportunity which is rightfully theirs; and they would never receive anything without continued sacrifice, which many were becoming weary and resentful of having to give.

It is why he moved to advocating for all who were poor. As King was working to get Black and White Americans to see their commonality, he felt that those who dealt with the effects of poverty had the best chance to find this common ground. He called all to reevaluate their priorities, and whether they were in line with the Christian teachings of love rather than the Nietzschean teachings of the will to power, where power is more important than justice because it gave one the ability to obtain gratification for oneself.

King tied his criticism of the militarization of American policy directly to the need to help those who are in need in our own nation, claiming that if we spent 10 years on poverty eradication what we spend in 1 year on military expenditures, we could change the dynamic of those in our nation.

He felt that this reprioritization of spending could help us regain the soul of our nation.

These are the cautionary tones he is striking after seeing the effects of poverty on Black Citizens in the North:

“When scientific power outruns moral power, we end up with guided missiles and misguided men.”

“We have allowed the means by which we live to outdistance the ends for which we live.”

These words, written in the late 1960s, echo powerfully today. His warnings, had they been heeded, could have led to introspection about who we wanted to be and led us to make different choices, but we have continued in the path of inertia.

Part of the reason for this is that right after King is murdered, the civil rights movement fractures and loses the influence it held for a time. Ralph Abernathy, another pastor who has been with Dr. King from the beginning, attempts to lead the Poor People’s Campaign, a march on Washington of those in poverty, but it fails quickly.

This is an area where one may question Dr. King: why did he not have a “Timothy” or “Joshua” — that is, a successor he had been preparing to take on his role after his death, as he had been expecting? We cannot fully know the answer to this. Perhaps King tried to groom many instead of one. Perhaps he never found one person he felt could follow in his footsteps. His role of leader to the movement was not calculated, rather it seemed the work of providence. Perhaps Dr. King felt that only God could raise up his successor.

It is also possible that King wasn’t looking for someone in the black community, but rather someone in the white community who would take on a role of leadership and influence that neither King nor anyone near King would be able to engineer. For a time, it seemed he looked to JFK and RFK as possible partners, but neither moved into that position prior to their own assassination.

There have certainly been voices in white America calling for reconciliation, but none have been able to inspire the white community to engage in a sacrificial nature as did the black community in those years. This is why King was so often disappointed in the white church leadership of his day. He felt that the Gospel had the power to lead people into humble, sacrificial reconciliation, but the white church often reflected culture rather than attempt to lead it.

So where does that leave us as we continue to live out King’s fears? Where, in fact, can we go from here?

Would King have liked Occupy Wall Street? Would he have liked Black Lives Matter? Perhaps. But the issue — as he dealt with from Carmichael and in Memphis — is that everything sooner or later gets co-opted. Others will take it and make it their own, to advance their own purposes. We must have an anchoring point. King constantly pointed to Jesus as this point. I believe he would ask people of faith to look for ways we can serve the downtrodden and broken hearted.

In Acts 1:8, Jesus tells his followers to go share the news of God’s great love to the ends of the earth. Paul, who had been entirely prejudiced against those who did not agree with him became one of the greatest proponents of reconciliation between all peoples after he encountered Jesus.

King preached often about blood: he said that there were four primary blood types, and those blood types were found in every group of people. We are the same, he was telling us all. Our differences are literally only skin deep. If we will but see people for what they are: children of God, we could overcome these differences. The church is where he gained these values and preached them to others.

Let those of us who have ears to hear, listen and respond accordingly. For as time has proved, this will not improve automatically.